He did not think of himself as a maker of art yet, not even the hint of one. But it was about then that for some reason Stoney borrowed a friend’s lathe and felt the rightness of it. Still, he did not suddenly smack himself on the head and declare himself to be an Artist: “I didn’t decide to be a sculptor,” as Stoney puts it. “I decided to make work on a lathe.” Fortunately, he was not an especially good bowl turner (according to him), or else the world today would have many additional so-so bowls, and far fewer Stoney Lamar sculptures. At last he began to really think about the lathe, to think about what it meant to geometry and line, and the way that we see the world. Now the drive grew in him, now he knew what he wanted to explore, and remarkably enough, Susan agreed to pack up their two young daughters and head to New Hampshire so he could serve as a wood turner’s apprentice. By the mid-‘80s Stoney and Susan were back in North Carolina, where he was creating work, being accepted to his first shows, and making early sales.

You cannot talk to Stoney about his early career for even a few minutes without him bringing Susan into the conversation. It was she who acknowledged the potential in him. It was she who not only allowed him to pursue his work, but encouraged it — demanded it. “You need to do this,” she told him. And so for years they lived below the poverty level, with Susan working at a bakery, drumming up catering jobs or doing whatever else helped keep the family afloat. Ask Stoney for the secret of whatever success he has enjoyed as a creator and he replies: “What’s really important is to be married to someone who doesn’t have to help you cash a regular paycheck.”

This is a biographical sketch , not a critical discussion of the work — there are others writing about that with considerable more ability and knowledge. Suffice it to say that he has been exhibited constantly ever since, that his work is in public and private collections across the U.S. and beyond, that he has won numerous awards, that he has lectured, taught, presided over workshops, served as artist in residence. He has been a board member of the American Craft Council, president and board member of the Southern Highlands Handicraft Guild, a founding member of the Association of American Woodturners, and president of the Center for Craft, Creativity and Design. Among many other things.

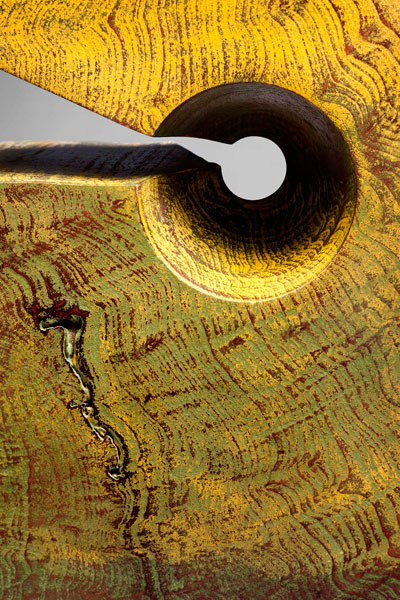

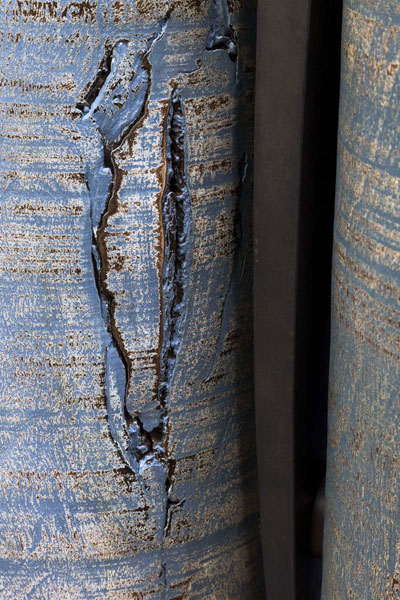

He produces his work in a studio in Saluda, North Carolina, about 35 miles southeast of Asheville. Saluda is a city of 700 where his father took his final church, and where he and Susan have lived ever since. Here they raised two daughters in the house they built up the hill from the studio, and where they now preside over a growing flock of grandchildren with love and befuddlement. As his career evolved and his range expanded, so grew the shop’s array of equipment, the drill presses, saws, winches, metal-benders, monstrous lathes, arc-welders, compressors, benches crowded with hand tools, walls of drawers. All manner of wood and metal pieces lean against the walls and fill the corners — work in progress, work abandoned, work under reconsideration, work that might or might not turn out to be interesting, work that has not yet not told him (as he puts it) what it is supposed to be. Lanky, gray headed, usually with goggles or a welding mask perched atop his head, Stoney at work gives the impression of a man puttering, and puttering some more, absent-mindedly, but who is in fact deeply absorbed in the next decision to be made, before the next hard, physical, irrevocable putting of machine or tool against material.

This brings us to the current stage of Stoney Lamar’s career, and its rather rude introduction. In 2009, he was diagnosed with Parkinson’s — the inexorable, progressive loss of control of motion. Parkinson’s is the cruel and perfect nemesis for a sculptor, in the way that a composer might go deaf, or a painter blind. For an artist whose life’s pursuit has been the captured expression of kinetic energy, the study of controlled line and frozen motion, what challenge could be more profound? Stoney himself wonders whether his creative self, his body and his subconscious, were aware that Something Was Up long before any doctor told him, given that new themes of stability and instability, control and lack of control, had already begun to emerge in his work, seemingly of their own will. In these years since the diagnosis he has worked like never before, pushed his art to new places with new concepts — and has by general consensus produced some of the best work of his career. “Movement,” he says with a wry grin, “has become increasingly theatrical.” You can tell that he is honored, but also a little worried, by this whole career-retrospective business, lest anyone confuse it for a coda or an ending. And rightly so. Serendipity should be allowed to run its course.

Howard Troxler

Saluda, North Carolina